Are Grievance Redress Mechanisms Mere Paper Tigers?

By Ludovico Alcorta, Tom Kirk and Annette Fisher

This blog explores what we know about grievance redress mechanisms in the Global South. A recent study by the FCDO-funded POTENCIAR programme in Mozambique provides a renewed perspective, alongside academic literature and experiences of designing grievance redress mechanisms for health programmes in Pakistan and South Sudan.

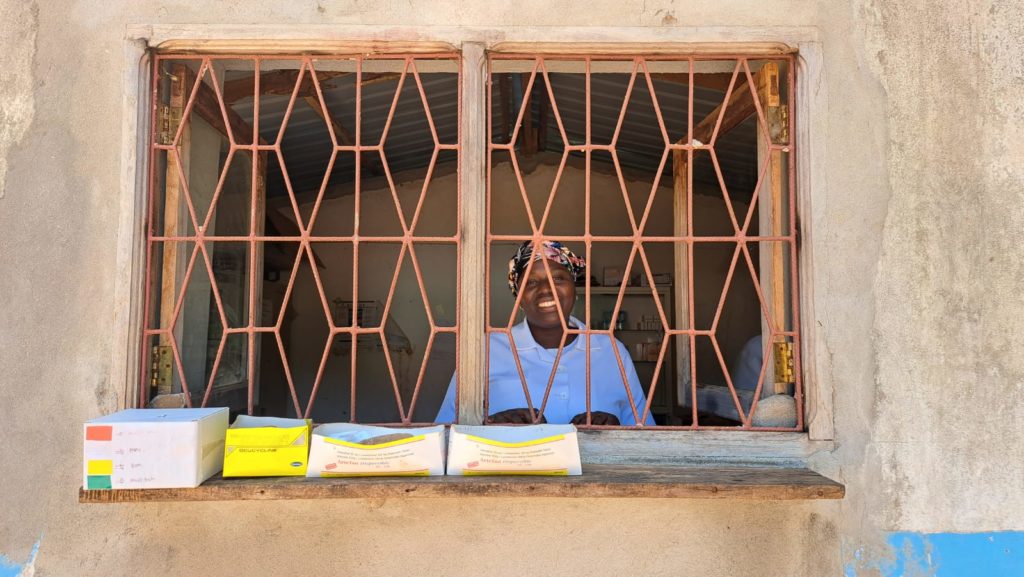

Photo: Satisfaction-box at Itoculo Health Facility, Monapo district. Users of the health centre allocate notes of the colour green, yellow, and red in the box to indicate their level of satisfaction with the service. This way of sharing the users’ experience is more accessible and carries less fear of retaliation. POTENCIAR is working with Co-Management Committees in Nampula and Monapo districts, Nampula province to improve grievance redress processes and thus the quality of services for users.

Grievance redress mechanisms (GRMs) enable citizens to record complaints about the poor provision of a service, public good or duty. For example, citizens may raise issues with the way they receive medicine in a health facility, the state of roads in a neighbourhood or discrimination by a police officer.

GRMs provide systematised processes for resolving such complaints. This may be done immediately by righting a wrong, communicating what actions will be taken in the future or explaining why something cannot be resolved in the expected way due to wider circumstances. This is called ‘closing the loop’. Whilst it is essential to not unduly raise citizens’ expectations, it is also important to understand whether GRMs can be more than powerless paper tigers.

GRMs – such as complaints boxes, help desks, community forums and call centres – are often seen as ways of empowering citizens to raise their voices. The goal is to realise their rights, elicit responsive governance, improve service delivery, and state-society relations.

In recent years, many governments in the global south have implemented GRMs to monitor and improve the provision of services, often with support from donors. For example, in Mozambique’s health sector, the current National Strategic Plan (2014 -2024) refers to the intention to “improve the quality of the services provided, through the guarantee of humanisation in care based on user-oriented services”. Naomi Hossain and colleagues point out that this phenomenon has paradoxically occurred as the space for other types of civic action has been closing.

Why do complaint systems matter?

The growing move to establish GRMs raises questions about motivations: are they genuinely intended to offer opportunities for raising citizens’ voices (especially at a time when other avenues are rapidly closing), or do they reflect a misplaced faith in bureaucratic solutions to poor service provision? Worse, are they driven by the need to fake responsiveness or to divert, dilute and quell citizens’ anger (a good example from universities)?

There are a range of ‘good’ reasons for establishing GRMs from both the government and citizen’s perspective:

- Technical considerations that view feedback and resolutions as a way to improve public services.

- Increasing demands from citizens for accountability and the humanisation of services that have long operated with impunity.

- Progressive governments may install complaints systems to tap their democratic potential, hoping that citizens will form participatory bodies to help govern them and advise duty bearers.

- Intra-governmental motivations for using citizen-generated data to monitor agencies and actors within the government

As should be clear from at least two of these, GRMs are not only a matter of technical design and information flows but they need to also carefully consider power relations.

Designing for a ‘complaints’ ecosystem

The existing literature on GRMs in the Global South is mostly descriptive in nature, with little analysis of how collected complaints are used, nor the impacts and outcomes of responses to them. Furthermore, the former tends to be found in donor funded project documents rather than governmental reports or academic studies (see here, here and here for good syntheses). Nonetheless, some emerging lessons can be discerned for developing an ecosystem where complaints are addressed:

GRMs should be designed with existing cultures of and community structures for complaint raising taken into account. This requires research on the wider context, including the laws and duty bearers, governing service provision, and potential users of any planned accountability mechanisms. The results will point the way towards what is possible in different settings and when adjacent initiatives that work on creating ecosystems conducive to GRMs may be needed.

This was brought home during the design of a GRM for the World Bank funded Provision of Essential Health Services Project in South Sudan. Research suggested that people prefer to complain through community representatives than as individuals. It also revealed that local government officials may be disinterested or overly punitive when complaints are brought to their attention.

In the case of Mozambique, POTENCIAR’s research indicates that community liaisons or local leaders are the main channel through which people express their grievances on health service delivery, in part due to high illiteracy rates and the inaccessibility of other more formal GRMs, but in part also due to the existing informal culture that is particularly prevalent in the context of rural Mozambique.

GRMs staffed by and linked to community members and existing community organisations are more trusted. Put another way, GRMs must be owned by the users of the services they are designed to improve. Where possible, GRMs should seek to employ local community members or be integrated within existing structures, such as civil society organisations and functioning service users’ groups. This may require training them to understand the purpose and operation of new GRMs.

In Mozambique, there is a fear of repercussions when complaints cannot be lodged with a trusted member of the community. One of the requirements for processing complaints using formal GRMs such as complaints books and hotlines is the identification of the complainant, which often deters users from using these mechanisms. Even liaisons between the community and health facilities, such as co-management committee members, are not wholly trusted at times, due to their proximity with service providers at health facilities.

For Pakistan’s Empowerment, Voice and Accountability for Better Health and Nutrition, researchers worked with community groups that were mandated to monitor and report on the provision of health services. They were made up of volunteers from local communities. Similarly, in South Sudan, researchers engaged Boma Health Councils consisting of local customary leaders to fulfil a similar role.

GRMs should have multiple routes for raising complaints. In some contexts, citizens do not have the capacity or means to lodge complaints through common methods such as writing, telephone helplines or internet platforms. Furthermore, they may actively fear face-to-face meetings with service providers or users’ committees made up of local authorities. Accordingly, GRMs should offer multiple safe ways to lodge complaints, ensuring that they are inclusive of diverse capacities and hidden power structures.

This was clear from exploratory research in South Sudan that suggested some groups are excluded from accessing customary authorities and, thereby, Boma Health Councils. To address this, researchers trained women and youth representatives to sit on the Councils, ‘Women’s Accountability Champions’ within communities and community health workers to sensitively receive and pass on complaints. Here, discretion, anonymity and verbal communications were key.

In northern Mozambique, POTENCIAR identified multiple GRMs present in health facilities, namely as complaint and suggestion boxes, complaint books, co-management committees, and telephone contacts. There is also a strong guiding policy framework in the health sector for GRMs. However, authorities need to recognise that those who operate these GRMs have to become more aware of the relational and power-related obstacles to users utilising these GRMs, and that they need to be adapted to make the more amenable and user-friendly for the most marginalised and powerless users.

GRMs require the buy-in of frontline staff and those duty-bearers that govern them. Front-line may perceive GRMs as an extra burden to workloads or as unwanted surveillance mechanisms. Accordingly, the benefits of GRMs must be explained to them, and incentives to collect and respond to complaints offered. Similarly, it is crucial that duty bearers at higher levels, from senior civil servants to politicians, are interested in the functioning of GRMs. This can give them the ‘teeth’ often needed to ensure poor performers improve or are sanctioned.

In Mozambique, POTENCIAR observed several health providers and authorities who understood the need to improve both the humanisation of health services and the mechanisms for managing complaints. Leaders of health facilities and co-management committees expressed an interest in acquiring more training and learning from the experience of other health facilities in the country. However, there is a fear on the part of service providers that receiving more complaints and grievances without the ability to offer improved services, will lead to stronger feelings of unmet expectations within the health sector. To address this concern, the promotion of mutual learning with other contexts should include experiences that show how the strengthening of grievance redress mechanisms may have contributed both to the improvement of working conditions of health providers and to an increase in the level of user satisfaction with the quality of the services received.

In Pakistan, this was achieved by inviting duty-bearers to meetings at different levels of governance with citizens that had raised, and were monitoring, the resolution of complaints. This was especially helpful when politically sensitive issues were being discussed and it was clear they needed to be escalated to those with the power to act. Furthermore, regular face-to-face interactions between complainants, service users and duty bearers provided to be the grease that ensured the mechanism worked and trust was built between these groups.

Unlocking the potential of GRMs

What does this mean for those who want to throw away the paper tiger and harness the transformational potential of GRMs? It is clear that GRMs are not quick fixes. POTENCIAR’s work on GRMs in northern Mozambique shows that progress takes time, because behaviours and attitudes are not easily altered, nor sustained. Rather, GRMs are embedded in the power and politics of the places, institutions, and state-society relations they seek to change. Their design must account for both the demand (raising complaints) and supply (responding to complaints) sides of their functioning. This entails securing buy-in from citizens and duty-bearers, building their capacities where necessary, and always ensuring safety is prioritised. Importantly, GRMs cannot be faceless. They must create opportunities for citizens to engage duty bearers and, in turn, duty bearers to explain the way they govern. This should go some way to ensuring the trust in GRMs is built and that they fulfil their potential to transform how and by whom services are delivered, in Mozambique and beyond.